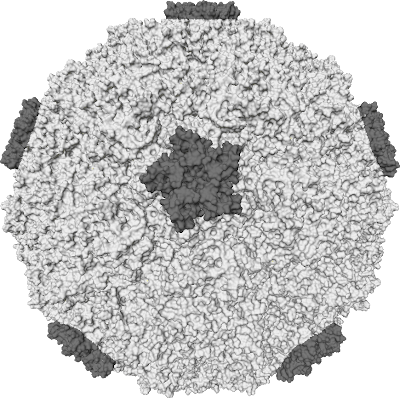

After diagnosing me, Cynthia grabbed a nice big picture book and flipped to a page with the following picture:

As a child, I was considered a very picky eater. I hated vegetables. I’d preferred to stay away from fruit. Mostly, I just wanted pizza and soda. Even during my teenage years after I’d been diagnosed as diabetic, I continued to mostly eat terrible foods. I’m really not certain how I got over it. One day I just started buying groceries and cooking for myself, and I began looking much more closely at everything that was going into my body.

This transition to caring about what I ate also coincided with completion of my bike ride across America. It is mostly true that you can ride your entire bicycle across the country all while eating mostly junk food. I didn’t quite do that. Mostly I ate a bunch of whole grains, peanut butter, jam, nuts, veggies when available, and a lot of pasta. Oh, and Clif Bars (yes. I can go on at length about qualities of each and every flavor). And the pasta was probably mostly a result of it being very cheap to make a lot of, as I was eating 5,000-7,000 calories a day. But I began eating less and less meat just because it’s a pain to obtain and cook when you’re beating it down the road 70-80 miles every day. But the point is I felt great without it. And so I when I finished the trip, I continued not eating much meat.

And then, one day, I was grocery shopping and decided I was going to stop eating meat. Granted, I considered the idea for a long time, but that was it. The important key here is the reason why it was so easy for me to quickly make this decision: I had already arranged a nutritious diet around eating very little meat. I did not just remove meat from whatever I would normally eat. I replaced my regular sources of meat with a lot of protein and iron sources that were not from meat. And iron and protein are mostly what meat provides to our bodies.

In practice this means a lot of beans, nuts, and leafy green vegetables (think spinach and broccoli). It’s not that difficult when you are making sure that you’re eating healthy. And most of us know what that means. We just don’t always do it. So, I’ll refrain from rambling on about that.

There is a caveat to add here. There is a difference between iron from meat (heme) and vegetarian (non-heme) sources. Non-heme iron is not as easily absorbed by the body as heme iron is. So, vegetarians often have to eat more iron than non-vegetarians. There are certain ways to help get around this. Consuming vitamin C with your iron helps your body absorb it better. Sometimes, you just have to take an iron supplement. Mostly you need to pay attention to signs of anemia and go to the doctor if you’re afraid you’re showing signs for anemia.

My point here is that transitioning to vegetarianism shouldn’t be made quickly. You should consider carefully why you’re doing it (something I’ve chosen not to go into here) and how you’re going to make sure you get the iron and protein you will no longer be getting from meat. Making the transition slowly helps a lot too. I was on my “meat seldomly” diet for over a year before making the leap to vegetarianism. But if you’re not careful, you may end up like many people I’ve known who tried to eat vegetarian and then ended up giving up on the diet (because they thought all they could eat were PB&J sandwiches) and/or became malnourished. I think it’s a great decision to eat vegetarian. Just make sure it’s an informed, healthy decision.

But it means that if you’re going to train for a spring marathon, hate treadmills, and working out indoors, you’re going to have to deal with some freezing temperatures. And possibly some slippery ice. Oh, and just being cold. But wait! It’s not actually that bad.

Everyone has their own methods for surviving cold weather running. But there are a few guiding principles that I’ll outline with my own practices.

My current diabetes treatment isn’t quite the same as when I was first diagnosed. I no longer take insulin injections, but rather use an insulin pump to administer insulin into my body. It basically looks like an old school pager with a funny tube hanging out of it. That tube is connected to my body via a small plastic catheter at an infusion site on my stomach. On the other end of that tube inside the insulin pump is a reservoir of Humalog insulin.

Humalog is a type of fast acting insulin, like R. However, it is more rapid acting. Within 5 minutes of entering the body, it begins moving blood glucose out of the blood to cells. Its “efficiency” peaks about 45 minutes after injection and ceases any function after about 3 hours. R on the other hand takes about 45 minutes after injection to begin functioning at all. NPH, being a slow acting insulin, takes about 3 hours to start its job.

The strength of the pump is that it basically allows me to give myself tons of injections of tiny amounts of insulin. It accomplishes this by keeping that catheter in me at all times. Additionally, since Humalog is a fast acting insulin, if need be I can program the pump to alter my dosage with almost immediate results. With an injection, you have to either hope the amount of insulin you gave yourself earlier isn’t too much to incite low blood sugar (ie: hypoglycemia) or hope that it wasn’t too little to cause high blood sugar (ie: hyperglycemia), which may mean another syringe and injection. Basically with the pump, I have a little more inflexibility by way of having something attached to me all the time, but I get a little more flexibility in how I can treat my diabetes.

Now, to mirror the basal and bolus treatment I outlined with injections in the previous post, I administer insulin two different ways with my pump. The basal is done by continuously giving me insulin at a rate I program into the pump (usually quantified as a unit per hour, where a unit is scientifically recognized as 0.001 mL). This is important because sometimes you need less insulin at night than you do during the day or vice-versa. But ultimately it’s kind of a like an IV drip.

The bolus is taken care of by having the pump deliver extra insulin whenever I sit down to begin a meal. I do this by counting how many carbs I plan on eating and then using a ratio of insulin to carbs to figure out how much insulin to administer (eg: at dinner I give myself 1 unit of insulin for every 10 grams of carbohydrates I consume).

In between all of these measurements of insulin doses, I also have to keep an eye on my blood glucose with my (aptly titled) glucose meter. Ideally, I try to keep my glucose between 90-130 mg/dL (that’s milligrams per deciliter). That’s considered a roughly normal range and keeps me feeling all right without any symptoms of hypo or hyperglycemia.

There are definitely a lot of caveats and changes I make to this formulation given circumstances (eg: using my pump to treat glucose levels above 130), but basically this is my life with diabetes. I promise it’s not as bad as it sounds. If anything, I promise I can tell you the nutritional facts on just about any food you can throw at me. And it certainly hasn’t kept me from living a normal life.

I’m not certain what I did to piss off my body to the point to make it think attacking my insulin producing beta cells was a good idea, but I like to think I was innocent in the affair. What I do know is I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes on June 2nd, 1997 at the age of 10. Fortunate to me, because my younger brother had been diagnosed far earlier in his life, my mother took notice quickly when I began exhibiting typical symptoms of hyperglycemia (ie: excess of glucose in your blood). Particularly, I was perpetually thirsty (nothing will quench the thirst of a burgeoning diabetic), and I literally had to urinate every 15 minutes. She checked my blood glucose level to find it was far above that of someone with regular insulin function.

I was consequently diagnosed with type 1 diabetes before hospitalization from DKA became necessary; by far, the most common introduction most type 1’s experience in their introduction to diabetes. From that point on, I began the regimen of twice daily injections of NPH and Regular insulin to act in the stead of the insulin my pancreas no longer made. NPH insulin is a “slow acting” insulin and acts to treat the base level absence of insulin in diabetics. Basically, this just covers the constant removal of glucose from the blood that any person requires even if they are fasting.

R is a “fast acting” insulin you take near a meal time that works to remove the sudden influx of glucose you experience when you eat any meal featuring carbohydrates (ie: bread, grains, sugar, etc.). There are different types of insulin and ways to administer it, but the typical prescription’s goal follows the outline above: You need to care for the base absence of insulin in the body, and then you need to also have the insulin care for the influx of glucose due to eating. Respectively, we refer to these different utilizations as the basal and the bolus. I’ll get back to these in the next entry.

But I guess this is the point where I should talk about how my life was never the same after that day or something. And I guess in a noticeable way it did change, but the truth is I’m a rather pragmatic person, even at the age of 10. Sure I had difficulties controlling my glucose levels at times, especially in my early teens (we’ll get to that later), but I felt better if I controlled my diabetes (which really means controlling your glucose levels). And there’s nothing to do about it for the present. So, I just sucked it up and got on with my life. That was a lot better than pouting about it.

There are two specific types of diabetes. They are known rather simply as Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1 is an auto-immune disorder in which a person’s body attacks and destroys the insulin producing beta cells of the pancreas. Type 2 involves the development of insulin resistance and/or a relative insulin deficiency.

As several of you are probably aware, the occurrence of either of these scenarios is a big deal. Insulin is the only hormone in the body that facilitates the removal of glucose (in so many words, sugar) from the blood and its passage into cells (eg: muscle, liver cells, etc.). There are many and several problems associated with not having insulin complete this task. If you’re ever in a doctor’s office, they usually get thrown under the umbrella term of “complications.” There are the “acute” or short lasting problems of diabetic ketoacidosis (ie: DKA, imagine your blood literally turning into acid), diabetic coma, or the very common hypoglycemia that can ultimately lead to seizures; then there are the "chronic" problems most people hear about that result in heart problems, blindness, and loss of feeling in one’s extremities (ie: feet and hands).

To prevent these complications, the goal of any diabetic is maintain blood glucose levels as close as possible to those of a person with normal insulin function. I am in no way equipped to speak on all the different methods for doing just that. And different methods work better and worse for different people. In general, they are all combinations of the same things though: Exercise, frequent blood glucose monitoring, finding the right balance of diabetes related prescriptions for you, and paying close attention to what food goes into your body.

It’s often a lot to ask of someone to take care of all those things. But as a diabetic, you eventually learn that they are necessary steps in order to live a good, enjoyable life. And that’s usually worth it.

The real point is I barely know what I’m doing when it comes to training for a marathon. I have a few things going for me though. I’m not entirely a stranger to endurance events. In middle school and early high school, I was a tolerable mid to long distance track athlete. And in college, I raced (very poorly) as an intercollegiate road cyclist before packing my bags to ride my bicycle across America (note: east-to-west is the wrong way). But before two weeks ago, I had never run more than 7 miles at a time in my life. Nevertheless, here I am beginning the third week of my training plan.

Concerning my training plan, I’m following the Novice 2 schedule of Mr. Hal Higdon pretty closely. I haven't had the easiest time building up to the mileage necessary for the start of the plan, but I've gotten there and am getting ready to take it a little easier this third week.

| Week | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rest | 3 m run | 5 m pace | 3 m run | Rest | 8 | Cross |

| 2 | Rest | 3 m run | 5 m run | 3 m run | Rest | 9 | Cross |

| 3 | Rest | 3 m run | 5 m pace | 3 m run | Rest | 6 | Cross |

| 4 | Rest | 3 m run | 6 m pace | 3 m run | Rest | 11 | Cross |

| 5 | Rest | 3 m run | 6 m run | 3 m run | Rest | 12 | Cross |

| 6 | Rest | 3 m run | 6 m pace | 3 m run | Rest | 9 | Cross |

| 7 | Rest | 4 m run | 7 m pace | 4 m run | Rest | 14 | Cross |

| 8 | Rest | 4 m run | 7 m run | 4 m run | Rest | 15 | Cross |

| 9 | Rest | 4 m run | 7 m pace | 4 m run | Rest | Rest | Half Marathon |

| 10 | Rest | 4 m run | 8 m pace | 4 m run | Rest | 17 | Cross |

| 11 | Rest | 5 m run | 8 m run | 5 m run | Rest | 18 | Cross |

| 12 | Rest | 5 m run | 8 m pace | 5 m run | Rest | 13 | Cross |

| 13 | Rest | 5 m run | 5 m pace | 5 m run | Rest | 19 | Cross |

| 14 | Rest | 5 m run | 8 m run | 5 m run | Rest | 12 | Cross |

| 15 | Rest | 5 m run | 5 m pace | 5 m run | Rest | 20 | Cross |

| 16 | Rest | 5 m run | 4 m pace | 5 m run | Rest | 12 | Cross |

| 17 | Rest | 4 m run | 3 m run | 4 m run | Rest | 8 | Cross |

| 18 | Rest | 3 m run | 2 m run | Rest | Rest | 2 m run | Marathon |